by Bo Cheshire, Museum Intern

My father fit the bill of ‘mechanically inclined’; when I was 12 he designed a hydraulic lift to attach a motorcycle to the side of an 18-wheeler, and in the basement of our house he designed and built neon light systems. He enjoyed working on motorcycles and cars, and loved to think about and understand how systems worked. I grew up watching him tinker.

This curiosity has extended to me through the lens of the natural world, but I also love engineering and technology. One could just ask my wife about the state of unfinished projects in my garage to get the full view of my obsessions, so getting the opportunity to utilize 3-D printing in conjunction with this exhibit is a dream come true.

The idea sprang from Professor Ozolins during out first meeting as a group in February. When the problem of how we might best exhibit specimens that we couldn’t get casts for was broached, he mentioned that we might be able to print them; I volunteered for the project immediately.

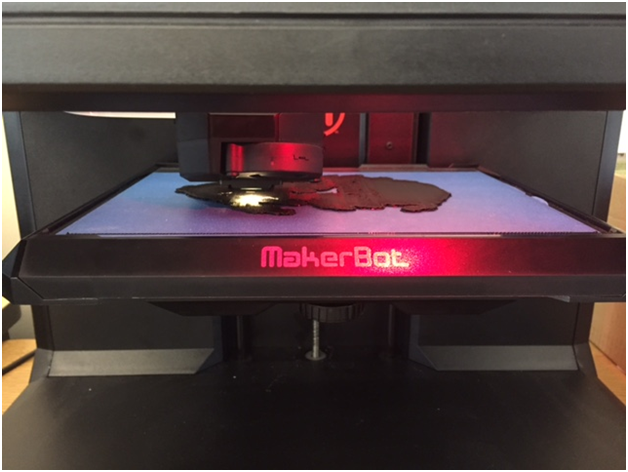

Professor Ozolins put me in contact with Dr. Nick Reeves, Professor of Biology and program manager for the STEM program at Mount San Jacinto College. Dr. Reeves, who has been gracious and generous with his time, was just as excited as I was to be printing hominin skulls. We met last month and he introduced me to the 5th generation Makerbot.

The 5th generation Makerbot 3-D printer.

I was pleasantly surprised at how easy and user friendly the system was. In most cases it was as simple as uploading a file, providing a little editing and manipulation, review, and print. My initial run was a small block in order to train me on the software and provide a proof of concept that the technology indeed printed exactly what we asked it to.

Next, we set our sights on the Homo naledi specimen, perhaps the newest and most exciting find in paleoanthropology in the last couple years. To place that statement into perspective, the principal investigator for H. naledi, Dr. Lee Berger, was just named as one of Time Magazine’s 100 most influential people for this year.

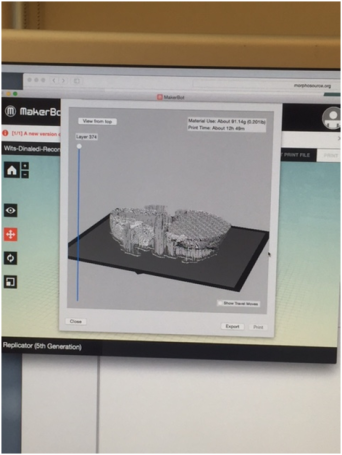

The Makerbot software in action.

One of the great things Dr. Berger has done is provide all of his research and castings in an open source format. This allows wannabes like me to access the materials and print the models. So in order to assess the technology’s ability to deliver quality models, we selected a reconstruction of the H. naledi skull and shrunk it to 1/12th the original size. That initial printing went flawlessly, and encouraged, we decided it was time to scale up the model.

Our initial try at a full size H. naledi reconstruction was estimated to last 12 hours; both Professor Reeves and I were excited but cautiously optimistic. When I arrived the next day I found only the lower third of the specimen had printed. As with any technology there are bound to be hiccups. Undaunted, I checked all the potential error points and found that the full size model hadn’t completely loaded, leaving us with the bottom third. The printer had done exactly what it was supposed to.

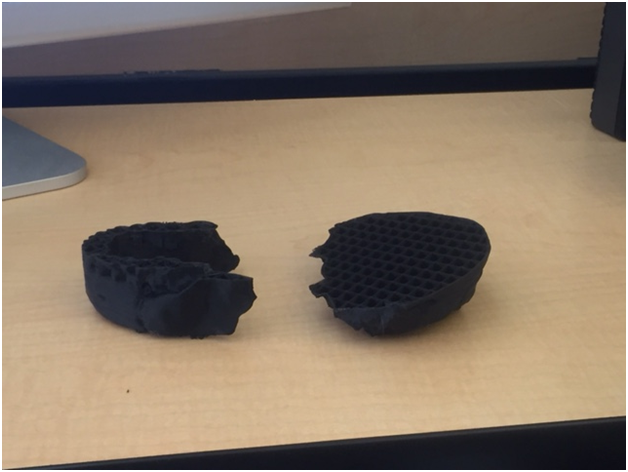

The first failed attempt.

After an update to the software, Professor Reeves loaded the printer for another run at the full size skull. Now estimated at 26 hours, it was set to run over a weekend. That Monday morning, I was full of anticipation, and after my first class I checked my email. Success!

The finished 3-D printed skull.

Being able to utilize this technology is going to allow us to share an important new find in paleoanthropology with the community. It allows us to go beyond the photographs and drawings that we may have otherwise used and provide the people who visit something tangible, a piece of our collective heritage that you touch and examine for yourself. I’m excited for how we’re incorporating this work into the exhibit, and am looking forward to finding new innovative ways to utilize this technology.

It would be certainly interesting to see how far this technology can be pushed. Could you make an entire skeleron, since most of it is online?

LikeLike

Hi Adam, this is Bo.

Let me start by saying that I’m a big fan of your blog. It’s informative and a blast to read, so thank you for taking the time to publish it. Now to your question. The short answer here is not now, but maybe real soon. The initial problem is that of the 90 files published of the Homo naledi specimen, only 15 are actually printable STL files. The remaining 75 are 3-D scans that can only be viewed and manipulated on a computer. I will admit that by no means am I an expert in this technology, but I’m optimistic that I can find a way to convert these “regular” 3-D scans to something printable. The basic internet searches I’ve conducted are promising, with a few websites claiming to be able to do this, but to be honest I’ve stayed pretty busy thus far printing the available files that I know are easy to do.

Beyond the file dilemma there is the fact that the printer I’m using would not be able to handle some of the larger dimension files that it would take to model an entire skeleton. In fact, I have already run into this problem: a printable model of the Australopithecus sediba skull is too large for me to print full size. This is owing to the 3-D scanning being completed when It was on a dirt pedestal. I can remedy this by changing the scale, and if I do eventually push to reconstruct H. naledi I may have to scale it.

All of us here are nerding out about these printings, and I’m sure with the level of enthusiasm we have, we’ll soon overcome these challenges. At the very least we have a really cool skull to look at. Thanks for your question.

LikeLike

That all sounds fascinating. But there’s also the issue of the fact that no single individual has more than (iirc) 10% of their skeleton preserved. Nevertheless the entire skeleton is there, between them all. If you were able to find a big printer and convert the various files, do you foresee any issues with merging these different skeletons together. Or might it be easier to do it this way, versus the more traditional approaches of trying to “guesstimate” what a complete skeleton might look like.

LikeLike

It’s not unusual to make a composite reconstruction of an extinct species in which the reconstruction is made up of portions of different individuals, especially for exhibit purposes. Complete individual skeletons are almost never found for any species. Having good 3D scans and printers makes this easier than it used to be, because the scan can be digitally altered so that it fits the composite better (for example, a bone from another individual can be enlarged or reduced, or a mirror-image can be printed as needed). However, it is a bit more complicated than that to make a good composite reconstruction. Members of a species can vary considerably from one individual to the next, many animals show significant sexual dimorphism (meaning the sexes are quite different in both size _and_ shape), and nearly all vertebrates exhibit allometric growth, meaning that as they grow during their life cycle they not only get larger but their proportions change. These variables all have to be considered when trying to produce a composite skeleton.

LikeLike